#Exhibit of the Month #Exhibit of the Month

June 2023

Political prisoner coat

With the establishment of the Soviet regime after the territorial abduction, the Red Terror broke out in Bessarabia. Starting from June 28, 1940, on the territory of Bessarabia, then of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (August 2, 1940), state bodies carried out a series of mass political repressions - under the pretext of political, social, religious and national reasons - in the form of deprivation of freedom, deportation, expulsion and other coercive measures. The first victims of this terror were the national elites: mayors, teachers, judges, lawyers, officials, former members of the Council of the Country, accused of "anti-Sovietism", "counter-revolutionary activity", belonging to political parties in Romania, etc. They were the target of the first arrests and imprisonments of the Soviet repression organs. Later, from 1941, the deportations of the native population to Siberia and to labor correction camps followed, the deportations of the civilian population from July 5-6, 1949, as well as those from April 1, 1951. According to the data of the Commission for the Study and Assessment of the Totalitarian Communist Regime in the Republic Moldova, established on January 14, 2010, the number of victims deported and subjected to repressions in the years 1929-1951 was assessed at over 90 thousand people. In a barbaric way, the repression bodies also attacked the participants and supporters of the resistance movement in the SSR, considering them state criminals, traitors, bandits, robbers. Leaders of resistance organizations were usually sentenced to capital punishment by firing squad, and active members to 25 years in prison, serving their sentences in labor camps and prisons. The territory of the Soviet empire was littered with a hideous network of correctional labor camps and prisons called the GULAG. Millions of people were imprisoned in the GULAG system of the Soviet Union, many of them remained forever in the lands of Siberia, in mass graves and cemeteries without crosses. Most of the camps were correctional labor colonies, where inmates were subjected to labor in mines or in the construction of roads, canals, railways or buildings. Prisoners worked under threat of starvation or execution. Tens of thousands died each year from grueling work, unbearable conditions, summary executions and inadequate food.

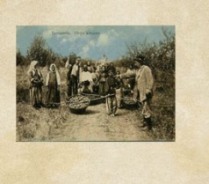

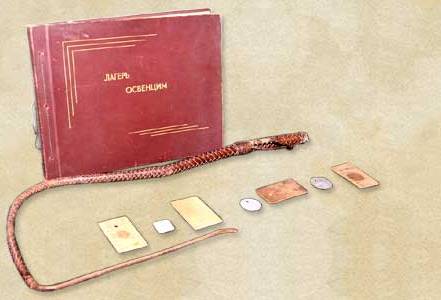

With the establishment of the Soviet regime after the territorial abduction, the Red Terror broke out in Bessarabia. Starting from June 28, 1940, on the territory of Bessarabia, then of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (August 2, 1940), state bodies carried out a series of mass political repressions - under the pretext of political, social, religious and national reasons - in the form of deprivation of freedom, deportation, expulsion and other coercive measures. The first victims of this terror were the national elites: mayors, teachers, judges, lawyers, officials, former members of the Council of the Country, accused of "anti-Sovietism", "counter-revolutionary activity", belonging to political parties in Romania, etc. They were the target of the first arrests and imprisonments of the Soviet repression organs. Later, from 1941, the deportations of the native population to Siberia and to labor correction camps followed, the deportations of the civilian population from July 5-6, 1949, as well as those from April 1, 1951. According to the data of the Commission for the Study and Assessment of the Totalitarian Communist Regime in the Republic Moldova, established on January 14, 2010, the number of victims deported and subjected to repressions in the years 1929-1951 was assessed at over 90 thousand people. In a barbaric way, the repression bodies also attacked the participants and supporters of the resistance movement in the SSR, considering them state criminals, traitors, bandits, robbers. Leaders of resistance organizations were usually sentenced to capital punishment by firing squad, and active members to 25 years in prison, serving their sentences in labor camps and prisons. The territory of the Soviet empire was littered with a hideous network of correctional labor camps and prisons called the GULAG. Millions of people were imprisoned in the GULAG system of the Soviet Union, many of them remained forever in the lands of Siberia, in mass graves and cemeteries without crosses. Most of the camps were correctional labor colonies, where inmates were subjected to labor in mines or in the construction of roads, canals, railways or buildings. Prisoners worked under threat of starvation or execution. Tens of thousands died each year from grueling work, unbearable conditions, summary executions and inadequate food.  A shocking testimony of the Soviet gulag is the exhibit "Political Detainee's Coat", displayed in this showcase. Museum piece - unique, it was purchased from the former political prisoner Vasile Cojocaru, domiciled in the city of Chisinau. It entered the heritage in 1995, during a period of intense activity of the museum's collaborators regarding the collection of pieces with the theme of communist repression. A shocking testimony of the Soviet gulag is the exhibit "Political Detainee's Coat", displayed in this showcase. Museum piece - unique, it was purchased from the former political prisoner Vasile Cojocaru, domiciled in the city of Chisinau. It entered the heritage in 1995, during a period of intense activity of the museum's collaborators regarding the collection of pieces with the theme of communist repression.

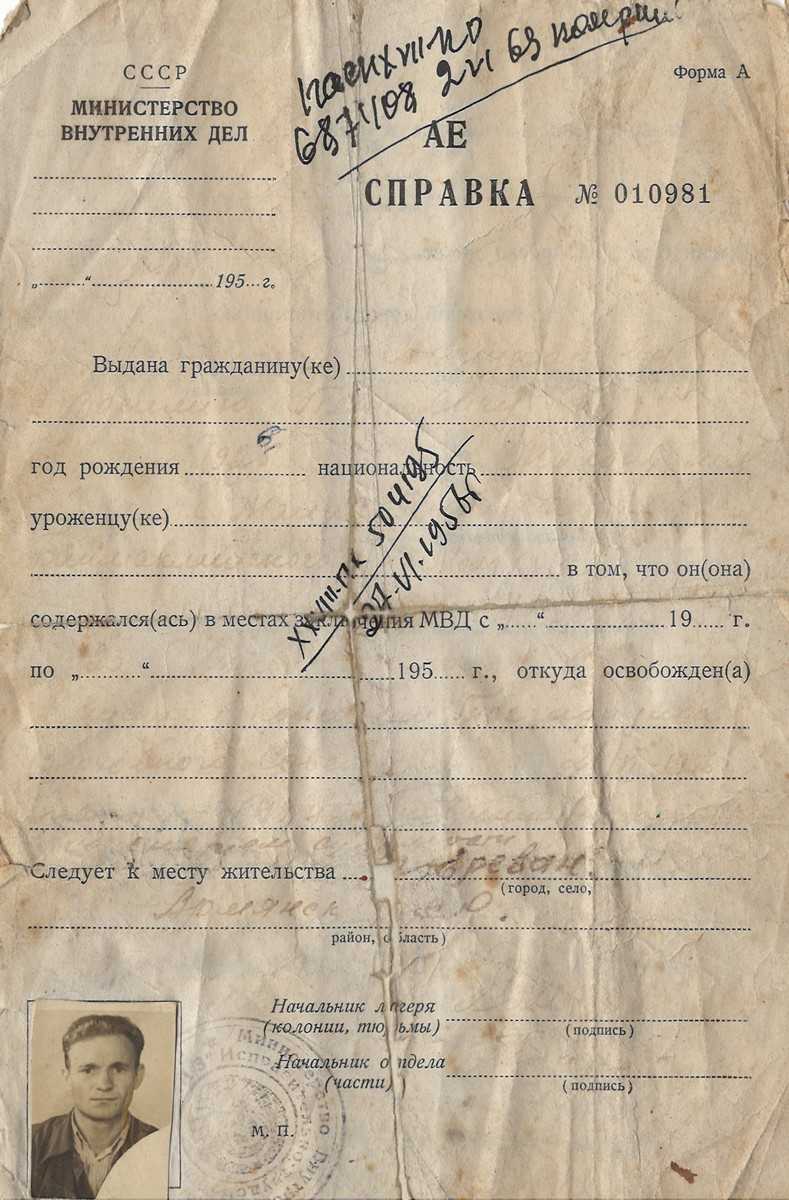

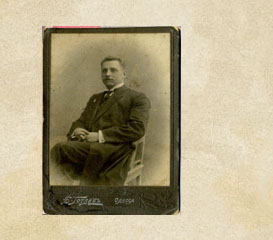

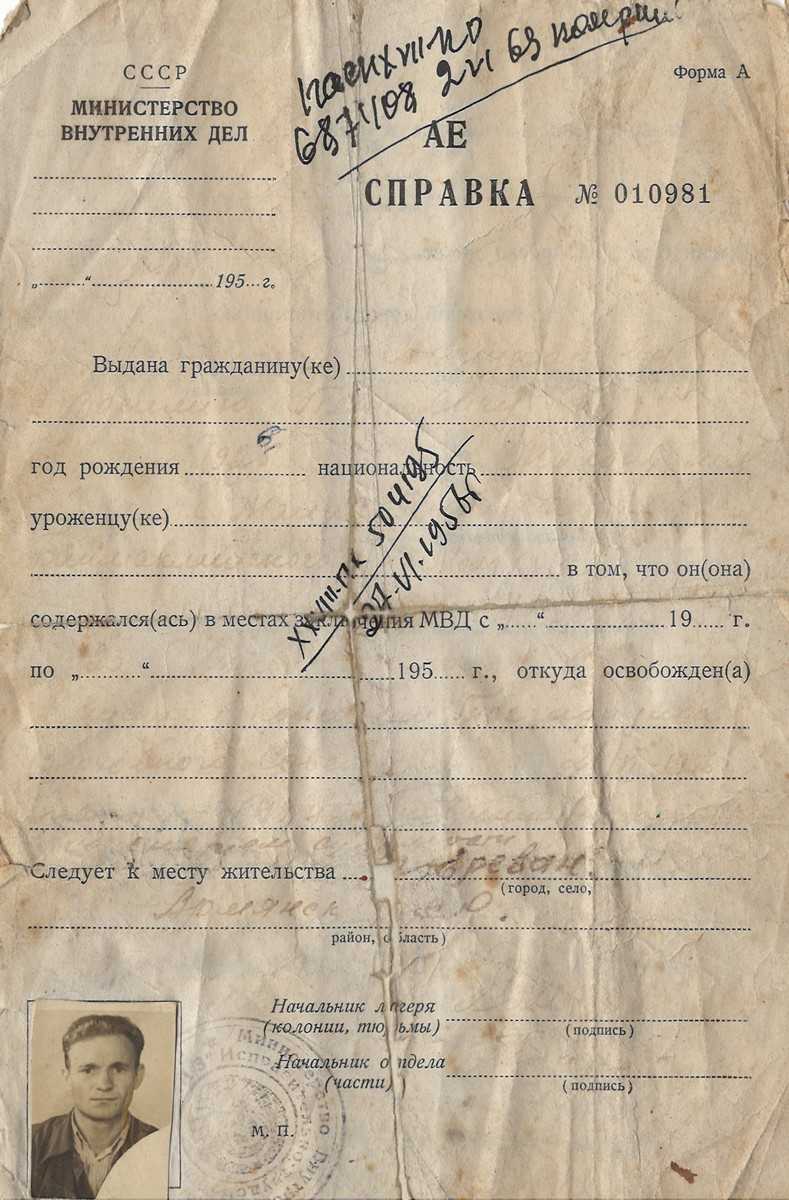

Vasile Cojocaru was born in 1926, in the village of Chioselia Mică, Baimaclia district (currently, Cantemir district). On June 16, 1951, he was sentenced to 25 years' imprisonment by the Military Court of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the SSR, according to article 54-1 (a) of the criminal code of the Ukrainian SSR - "treason", and escorted in a special camp in Kazakhstan, with prohibitions on rights and confiscation of property. Obviously, we ask ourselves the question: What guilt is hidden under this accusation of "traitor to the fatherland", which crippled his whole life?  In July 1941, his father, Cojocaru Petru Grigore, born in 1886, was arrested and qualified as an "enemy of the people" (he was a member of the National Peasant Party), all his wealth being confiscated. On August 15, 1942, as a "dangerous social element", he is imprisoned in the correctional camp in the city of Mariinsk, Kemerovo region, where he dies under unclear circumstances, most likely he was executed. Vasile, 14 years old, and his mother were left on the roads, without means of subsistence. Eventually, the house is returned to them and they start a new household. But in 1944 he was drafted into the Soviet Army and sent to the front line of the 2nd Belorussian Front, where he was wounded twice, becoming a war invalid, 2nd degree. Returning home in 1948, he found his mother on the road and ill. He dares to ask the authorities for part of the confiscated wealth, to which he receives a threat - that he will be sent in the footsteps of his father. For three years he was persecuted for this "daring", as in 1951, although he defended the Bolshevik country at the cost of his health, he was arrested and convicted. Here, in fact, is what is hidden under this accusation of "treason", imputed to this citizen. In 1956, he was released from detention and sent to Armenia, the city of Yerevan, the place of residence indicated by the camp authorities. For many years in a row he was pursued by the security organs, being far from home, as political prisoners were forbidden to return to their place of residence. Come home later. Through the certificate of 28.02.1992, issued by the Prosecutor's Office of the Republic of Moldova, he is rehabilitated at and restored to rights. On July 25, 1991, his father was also rehabilitated. In July 1941, his father, Cojocaru Petru Grigore, born in 1886, was arrested and qualified as an "enemy of the people" (he was a member of the National Peasant Party), all his wealth being confiscated. On August 15, 1942, as a "dangerous social element", he is imprisoned in the correctional camp in the city of Mariinsk, Kemerovo region, where he dies under unclear circumstances, most likely he was executed. Vasile, 14 years old, and his mother were left on the roads, without means of subsistence. Eventually, the house is returned to them and they start a new household. But in 1944 he was drafted into the Soviet Army and sent to the front line of the 2nd Belorussian Front, where he was wounded twice, becoming a war invalid, 2nd degree. Returning home in 1948, he found his mother on the road and ill. He dares to ask the authorities for part of the confiscated wealth, to which he receives a threat - that he will be sent in the footsteps of his father. For three years he was persecuted for this "daring", as in 1951, although he defended the Bolshevik country at the cost of his health, he was arrested and convicted. Here, in fact, is what is hidden under this accusation of "treason", imputed to this citizen. In 1956, he was released from detention and sent to Armenia, the city of Yerevan, the place of residence indicated by the camp authorities. For many years in a row he was pursued by the security organs, being far from home, as political prisoners were forbidden to return to their place of residence. Come home later. Through the certificate of 28.02.1992, issued by the Prosecutor's Office of the Republic of Moldova, he is rehabilitated at and restored to rights. On July 25, 1991, his father was also rehabilitated.

The clothes on display - the waistcoat and trousers - are part of the prisoners' summer clothes, which also included a round cap, which the museum does not have. They are made of thick cotton fabric. The vest has long sleeves, collar, closes with four buttons, having two patch pockets on the sides. The pants close with buttons, have two side pockets. On both pieces is applied the number "CEE 893" - the holder code of Vasile Cojocaru. Three capital letters and three numbers are written in black paint on a piece of white cloth. The prisoner's number was applied in four places on the coat. One number was applied to the cap, another - to the back of the waistcoat, the third - near the heart, and the fourth - to the trousers, above the right or left knee. These four places, in fact, were also considered as sighting targets, in case the prisoner escaped. The number also applied to prisoners' winter clothes (down jackets, padded trousers, hats). As for footwear, the prisoners wore - in spring, summer and autumn - a kind of large galoshes made of rubberized fabric, less often, kirza boots, and in winter - felt. Usually, new arrivals were given second-hand clothes - old stuff with a terrible smell. The exhibit has an indisputable museographic value. It gives the public the opportunity to see and understand the consequences of the establishment of the communist totalitarian regime in the SSR. By exhibiting it, we pay tribute to all the victims of the Red Terror in Bessarabia, on the eve of June 13 and July 5-6 - days when the two waves of deportations of our natives took place.

|

The decoration of these pieces is remarkable, featuring hand-painted "German flowers," one of the well-known styles of floral and plant decoration practiced by Meissen craftsmen since the 18th century. They were influenced by Chinese porcelain, which was often adorned with images of flowers and fruits. A distinctive feature of this decorative style was the "scattered flowers" arrangement, where floral elements were placed as individual blossoms or bouquets across the surface of porcelain objects.

The decoration of these pieces is remarkable, featuring hand-painted "German flowers," one of the well-known styles of floral and plant decoration practiced by Meissen craftsmen since the 18th century. They were influenced by Chinese porcelain, which was often adorned with images of flowers and fruits. A distinctive feature of this decorative style was the "scattered flowers" arrangement, where floral elements were placed as individual blossoms or bouquets across the surface of porcelain objects.